EARTH ISLAND JOURNAL

9 de agosto, 2023

Gabriela Verdezoto

This story, produced by InquireFirst with support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, was originally published by Montañas y Selva: Voices from the Andes and the Amazon.

YEAR 2020.

Soccer, beers, barbecue, shared sweat, teamwork. Laughter. Nine people with yellow rubber boots and machetes in their hands smile at the camera. Others, as if it were choreographed, weed a section of jungle with their bare hands to set up the field. In the background, a machine turns and cement covers the bricks that will support the construction of a communal house. The roof is made of zinc. Several men raise a wooden pole on which they install an electricity box. All the photographs speak of the joy of shared labor and community.

The company is Terraearth Resources and specializes in gold mining. But it has not always had that name. The company has a long history of changing names, activities, and shareholders.

On October 10, 2001, RBBPACAY-RIO VERDE S.A. was established in Quito as a legal, financial, and accounting consulting company. In June 2004, it received foreign capital from Merendon Mining Corporation LTD., which in turn has capital in Belize and is registered in Honduras. In July of the same year, it changed its name to Merendon del Ecuador S.A. In October 2004, it changed its corporate purpose, it stopped providing legal advice for mineral extraction. On September 29, 2011, it changed its name to Terraearth Resources S.A. In 2017, Peng YongMing and Wang Ye, of Chinese nationality, became the shareholders of the mining company.

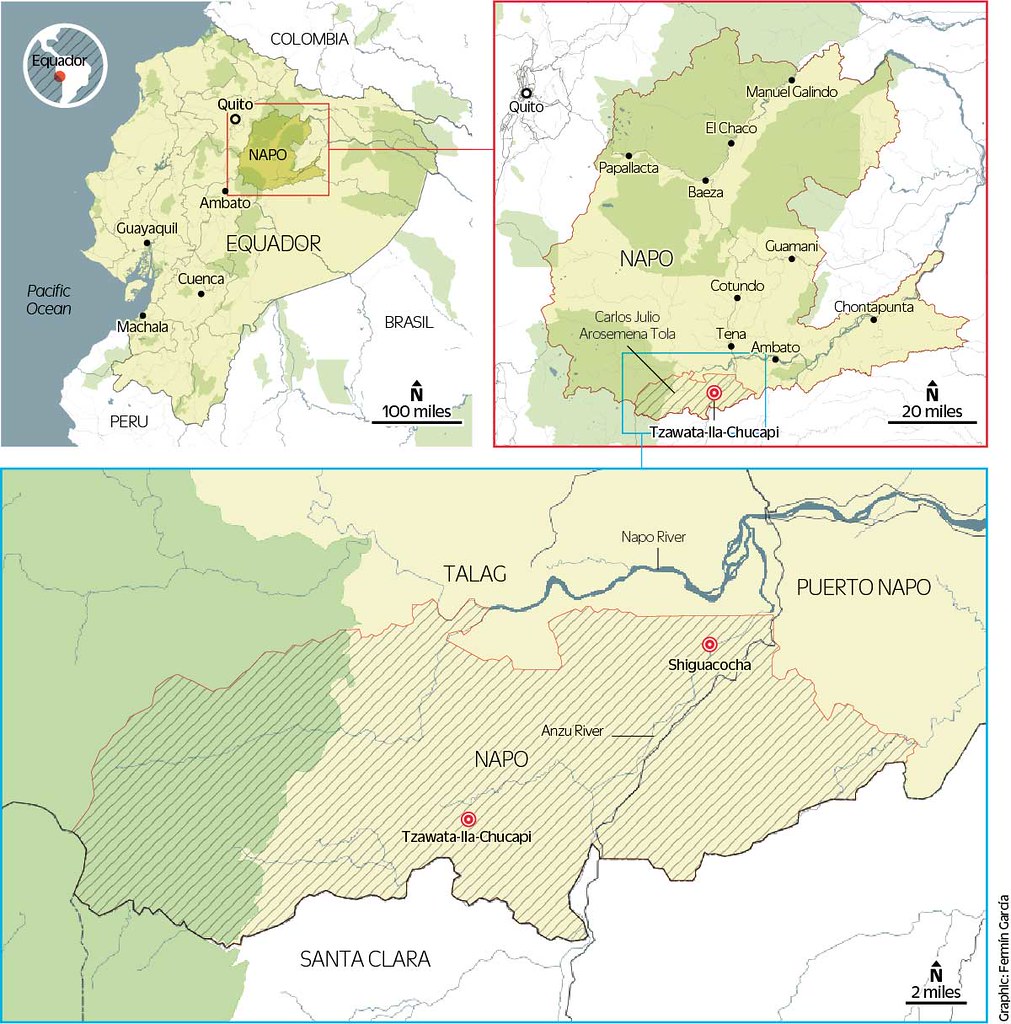

Shiguacocha is within Ecuador’s Regina 1S concession, which consists of 4,077 acres that the government assigned to Terraearth Resources for small-scale gold mining.

According to the MapBiomas Amazonia initiative, between March 2017 and March 2022, almost 700 acres of deforested rainforest and agricultural areas were identified in that concession alone — the equivalent of almost 400 professional soccer fields. Terraearth Resources blames illegal mining in its territories and the lack of government control for the increase.

Mineral extraction in Napo began more than 25 years ago. But between 2015 and 2023 it expanded by 300 percent, according to a multi-temporal comparison by the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP).

“If we look back, the first mining companies came to settle in rural areas inhabited by Indigenous communities that did not know what they were coming to do and, in addition, had no education. Some of them did not even speak Spanish,” says Andres Rojas, Ombudsman of Napo.

“The companies arrived offering work, favors, and money. They made the elders put their fingerprints on permits, documents, and contracts, or they bought the land from them at ridiculous prices. The people began to divide between those who benefited from the newly arrived companies and those who witnessed the painful destruction of their land, their water, their habitat.”

Does Legal Mining Exist in Ecuador?

“All mining in Napo is illegal,” says Rojas, “because legal procedures, environmental management plans, and remediation plans have not been complied with.” According to Rojas, there is not a single mining concession in Napo that has been granted with free, prior, and informed consent, and none of them have met the environmental guidelines established in the Environmental Organic Code and its regulations.

During the national strike of June 2022, which lasted 18 days, one of the main demands of the Indigenous sector was the implementation of the law and regulations that indicate how prior consent should be carried out. President Guillermo Lasso promised at the time to present a draft law on free, prior, and informed consent in a maximum of 100 days. Ten months have passed and there is still no such legal instrument.

On the other hand, Rojas insists that in 2010 the Constitutional Court made an analysis of free, prior and informed consent and set out the path to follow in order to issue the regulations. But neither the National Assembly nor the executive branch has taken these guidelines into account.

“The government cannot say that it does not have guidelines to carry out the consultation as long as there is no law, because the Constitutional Court has already given guidelines on how to carry out a consultation,” says the Ombudsman of Napo.

The truth is that no one has ever consulted any community in the province about extractive activities in their territories. The residents of Shiguacocha confirm this and say that decades ago, their grandparents were also convinced to exploit their land. They received gifts and “now nothing grows.”

At the top of a small hill near the community there is a large pasture, abandoned land that belonged to Terraearth Resources. After being mined more than five years ago, it was left like this — just weeds sprouting where nothing else will grow because everything underneath is polluted.

Fiodor Mena is president of the Association of Environmental Engineers of Ecuador and was, until April 6, 2023, zonal director of the Ministry of Environment, Water, and Ecological Transition. According to studies by the Association, the reforestation of 2.5 acres of the Amazon region damaged by mining would cost an estimated $57,467. Mena says that in order to avoid that cost, the companies prefer to abandon the fields. Without a science-based reforestation process, he says, the soil is left polluted and what grows there is not even useful for agriculture.

Thus, like that abandoned field, what remain are the old and forgotten mining areas. Mena says that the Ministry of Environment, Water and Ecological Transition has recognized, in its inspections, that these areas were not properly reforested. The Ministry has initiated seven administrative actions against Terraearth Resources. All of them are in the initial process, however, and the company continues to operate.

On September 23, 2022, Mena, as zonal director of environment since January 10, 2022, was a kind of mediator between the representatives of Terraearth Resources who were asking for permission to use the water of the Sinchuyacu River for their activities, and the social collectives that came to the hearing to urge that not a single permit be issued to Terraearth Resources. Studies by the Ikiam Amazon Regional University showed that due to the direct discharges the company made to the Chumbiyacu River, the river was declared dead in 2021.

At the meeting, environmental activists accused the company of polluting the rivers. Terraearth Resources’ lawyer, Daniel Cruz, acknowledged that there had been direct discharges of contaminated material into the water sources, but he alleged that the blame lies with illegal mining that invades the company’s concessions.

Hernán Lema, environmental consultant for Terraearth Resources insisted that all the environmental mismanagement, contamination, and death of the rivers is a sign that the government has not had the capacity to control illegal mining and that Terraearth Resources only provides work and permits for artisanal miners to wash the soil around their backhoes.

Outside the meeting room on September 23, 2022, residents of Santa Monica, a neighboring community of Shiguacocha, stood for three hours holding signs in support of the mining company. They were brought in buses. The manager of Terraearth Resources, Peng YongMing, in response to the demands of the social groups, at one point during the hearing shouted something in Chinese and the inhabitants of Santa Monica silently filled the hall of the offices of the Zonal Ministry of Environment.

There was an altercation between YongMing and an activist and Mena asked the villagers to leave. “Don’t let them treat you like this,” Yessenia Hernandez, representative of Napo Resiste, said to the Santa Monica community members at the end of the meeting. They lined up and followed a Chinese man in blue overalls who took them back to the buses.

Mena did not allow the mining company to use the Sinchiyacu River. “There were many inconsistencies in the reports, plus it had operational prohibitions,” he said with a slight smile.

“I also did not approve the certificate of non-affectation of water resources requested by Terraearth, and without this, it is not possible to operate,” Mena recalled.

That was one of his last decisions before being removed from office on April 4, 2023.

“How did you hold your position as director of environment of Napo for so long, being an environmental defender?” I ask Mena during a call.

On the Zoom screen, behind glasses that give him all the look of a scientist, Mena smiles and sighs before answering.

“There is a lot of pressure, yes, there is a lot of pressure there.”

The conflicts and pressure for territorial control between the mining companies and the locals are more frequent than it seems.

“There is no such thing as ‘good mining.’ The condition for this extractive activity to reach the territory is always violence,” says Mishel Baez, professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador, political scientist, and specialist in mining issues.

“The strategy is always the same: They look for a couple of families with whom they negotiate first. They give them jobs and economic benefits. It is what we call ‘technology of division.’ They know how strong the Amazonian communities are and, in order to take possession of the land, they must divide them,” Baez said.

“Another common practice repeated in all mining settlements is to take advantage of the patriarchal structure and offer trips, money and alcohol to the community presidents to reduce the resistance that generally comes from the women,” Baez says, confirming that the modus operandi has been the same in Argentina, Chile, and Brazil according to her studies.

Finally, Baez says it is important to note a new form of division that is related to the generation gap. Mining companies offer technology and money, and spread new ideas about progress to young people, turning them away from the defense of nature for which the elders are fighting.

All of this has occurred at Shiguacocha.

Since 2016, when Patricio Villamil took over the presidency of the community, he has been complaining to the Attorney General’s Office, the Ombudsman’s Office, and other community leaders that, in the more than 20 years of mineral exploitation in their territories, they have been offered everything and have received nothing. They are still poor, now without water and without productive land.

But not everyone agrees with him. There are communities that claim that mining companies such as Terraearth help them.

Raul Grefa is one of the representatives of the Santa Monica community, which supported Terraearth’s request to use the Sinchuyacu River. It is a neighboring town of Shiguacocha, with whom the community used to share the Chumbiyacu River. Or they still do, although the river is no longer liquid and crystalline, but a sort of swampy muddy flow.

The community of Santa Monica arrived by bus to support Terraearth Resources during a hearing at the regional offices of the Ministry of Environment. Photo courtesy of Montañas y Selva.

In 2020, a study by the Ikiam Amazon Regional University showed that the heavy metals concentration in the Chumbiyacu River is 500 times higher than acceptable levels. The study also found no sign of life in the river — not a single fish passes through what was once a source of fishing for the communities. Not even plankton survive in it, and the sediment is so thick that the sun’s rays cannot pass through.

Grefa accepts that mining is devastating everything in its path. “The Chinese polluted the Chumbiyacu River. It is true. And they have damaged our land,” he says. However, he insists that, given the scarcity in the community, it is preferable to earn a few grams of gold working with the company or, at least, to receive some water tankers. If it were up to him, he would “kick out’’ all the mining companies from his town and from the entire Amazon, but, since it is not possible, “we have to side with one of them.”

“It is the government’s fault for having signed the concessions. I have lived here for 60 years. In the past, the rivers were clean and full of fish, but now everything is damaged. We can’t even bathe in the streams anymore. The land is poisoned,” says Grefa.

The Ecuadorian government lost a 2022 lawsuit filed by 12 groups defending the rights of nature in Napo. The Provincial Court judge accepted the responsibility of the Ecuadorian government for failing to control the environmental breaches of legal mining companies, which left behind hundreds of environmental liabilities. The court gave the Ministry of Environment, the Ministry of Mines and the Agency for Regulation and Control of Energy and Non-Renewable Natural Resources (ARCERNNR) 180 days to implement a reforestation plan. This obligation expired in October 2022 without any environmental remediation. No ministry has commented on the issue.

On March 24, 2023, under legal pressure from the collectives, the judge of Napo recognized that the three institutions had not complied with the mandate, so in a new sentence he demanded that the ministers be removed from their positions and gave them a 24-hour deadline to comply with the sentence and the reforestation plan.

The Minister of Mines, Fernando Santos Alvite, said in an interview on January 23, 2023 that he did not know about the ruling of the Napo court and that he was going to request further information. The regulatory agency responded to our requests for information by saying that they will not give interviews until the new director, Patricio Bonilla, “absorbs” the information about the issues of the institution. The Ministry of Environment said that this resignation request is not valid and that they are in the process of creating a reforestation plan.

“So at least the Chinese give us a little work in their concessions,” says Grefa, adding that “there, hopefully, we can get at least a gram (of gold, equivalent to $45) from time to time.”

Grefa insists that he would agree with the departure of all mining operators from their territories. “If they leave, let them all leave, but not only the Chinese, who at least help us in some way.”

The Facebook page of Terraearth Resources constantly promotes the social contributions they provide to communities. For example, a post from August 26, 2022 reports that it delivered a 105-quart pot and 40 chickens to the community of Santa Monica to celebrate its foundation. The wide-shot picture shows the community members seated around the basketball court.

In another post from December 27, 2022, young men in blue uniforms smile next to company personnel. In a dozen more pictures, happy people can be seen receiving bottles of soda, garbage bags filled with gifts, girls with red Christmas hats, and several villagers signing the certificates of receipt of these gifts. Terraearth Resources personnel appear in all the pictures.

The most recent publication that reports on the company’s deliveries is dated April 19, 2023. It celebrates the 43rd anniversary of the founding of the Nueva Jerusalen community, near Shiguacocha, within the Regina 1S concession. In the main picture, the smiling, beautiful queen of the village poses next to a Chinese worker with several crates of beer at her feet.

“The bargaining chip for the destruction of the territory and community divisions has always been migajas,” the scraps or leftovers that are given to someone or that someone takes advantage of, Rojas insists, adding that offers such as drinking water projects, community houses, road opening, or, sometimes, just a few dollars, are enough to permit the machinery to enter and the mining operators to settle in to exploit the territory and take the gold.

“The mining companies’ strategy is to divide. They negotiate, buy or build a relationship with two or three families and create conflicts in the community. It is becoming their modus operandi,” says Jose Moreno, coordinator of the social collectives that fight against the environmental and social damages caused by mining in Napo. The groups he works with include the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of Napo (FOIN), Napo Ama la vida, the Confederation of Peasant Defense Councils of Ecuador, and the presidents of several communities.

Two days after the interview with Moreno, on March 22, 2023, he was attacked while he was with a group of military personnel in a raid in the parish of Talag in the Carlos Julio Arosemena Tola canton.

SHIGUACOCHA OBTAINED ITS legal status in 2008 with 40 members and, according to the bylaws, had to change presidents every two years.

“As we organized, we don’t even remember the idea of continuing with the legal status. We did everything by talking, in mingas [supportive gatherings of friends and neighbors to work together], in meetings between members. We got along well. There were frictions as in any group, but no serious conflicts until the Chinese arrived,” Patricio Villamil says.

Villamil, according to a document from the Council for Citizen Participation and Social Control, has been president of Shiguacocha since 2016.

“I did the paperwork to be able to formally request drinking water, sewage, and access roads from the authorities,” he says.

To date, they have none of this.

When he assumed the presidency, he began to demand that Terraearth Resources comply with its promises, such as providing jobs for the people in the community. He also sent complaints to the company when it discharged mining waste with high levels of heavy metals (lead, cadmium, zinc, copper, bromine, boron, and mercury) directly into the Chumbiyacu River. He complained about the children who began to get sick and about the devastated land left by the company when it finished “washing the soil.”

Washing the soil means removing all the layers of the jungle with heavy machinery until pools 33 feet deep are formed to extract — along with water, mercury, and other metals — the coveted gold. According to Aidde Arvizu, a geologist and expert in geophysics, geotechnics, soil mechanics, and mineral exploration, these waste liquids should be sent to treatment ponds. But in many cases, that does not happen and the waste is discharged directly into the river, as the Ministry of the Environment found during an inspection on February 3, 2022 in the Shiguacocha area.

Arvizu insists that if mining companies had good environmental controls, this damage could be prevented.

But that was not done in Shiguacocha. “And they leave the land like this, useless. Useless, poisonous mud, since it is polluted. What is going to grow there?” she asks as she points toward the boundaries of her father-in-law’s land.

She said this on a humid day in September 2022. Community members wanted to show the problems on their land. Two weeks earlier, they had a confrontation with the Santa Monica community, which wanted to make way for a crawler excavator. The inhabitants of Shiguacocha no longer want mining in their territories. They say they have witnessed dead and clogged rivers, acres of open, stony, and unsuitable soils, and even greasy puddles of diesel along the roads.

Patricio Villamil complained about all this. “They didn’t like the fact that I complained so much. They wanted us to settle for migajas and I didn’t agree. Since I became president of Shiguacocha in 2016, I was asking them to affiliate the colleagues who were mining around the machines. Once, I met with the manager of the mining company and he told me that if I do interviews and speak favorably about the company in the media, they would help us with the needs of the community. I told them I wouldn’t do that.”

At Villamil’s insistence, in 2020 — 19 years after Terraearth Resources was granted the concession — the company donated $9,000 in construction materials for the building of the community house. This was one of the most joyful moments in the rural parish in the Amazon. Together, community members built the house with pink walls, windows without glass, a silver tin roof, and a soccer field outside. Of that joy, only pictures remain.

On that Saturday in September 2022, the members of Shiguacocha gathered, deeply concerned, in the community house, not knowing that it would be one of the last times they would be there.

They talked about their sorrows and their regret for the violence with which the town has been plagued.

Antonia Aguinda recalled that when the machines began to work on their land, they surrounded a backhoe, and a colleague was almost killed. Aguinda described this episode several times, and each time, she wept.

“The biggest problem is “that our own communities, our own families come to insult us for opposing mining,” Norberto Urresta said in the stagnant heat of the Amazon.

“I don’t want compassion. I want justice for Shiguacocha,” young Natali Illapa insisted and recalled those weekends when everything was a party around the construction of the community house.

The soccer field was neglected. No one dares to play there anymore. That September 22, at the end of the assembly, they left quietly, without a trace of the emotions they experienced in that same place almost three years ago.

Dispute Divides Families

Quito, D.M., March 30, 2021

Subject: REGISTRATION OF DIRECTORATE AND INCLUSION OF MEMBERS OF THE KICHWA COMMUNITY “SHIWA COCHA” OF THE ANZU RIVER

Mr. Nelson Humberto Aguinda Andi

President in charge

KICHWA SHIWA COCHA COMMUNITY

In office

Yours faithfully:

Thus, begins a notification from the Human Rights Secretariat in which Nelson Aguinda is recognized as president of the community. In addition, it endorses the resolutions of an alleged Assembly held on February 21, 2021, among which is the reelection of Aguinda as president with 36 votes, followed by 14 votes for the second candidate and 10 votes for the third. The inclusion of 40 new members and the exclusion of 9 people from the community, including Patricio Villamil, were approved.

According to the document, the Assembly began at 3:10 p.m. and concluded at 2:20 p.m.

“There were so many inconsistencies that even the time was entered incorrectly. We were never notified about the meeting and, without explanation, they decided to kick us out of the community. There were people who had already voted before being accepted as members. Of the alleged 40 new members, less than five live in Shiguacocha,” said a visibly upset Villamil.

“But it seems that among the people who signed this document, the surnames Villamil, Aguinda and Gualinga are included,” I ask. “Is that correct?”

“That’s right, and they are my family and the family of other people in the community because that’s what the company did, it divided us. It is painful to have to fight against our own flesh and blood. They started to say that I was against the progress of the community and that I was not allowing them to benefit. I was trying to explain that they were just giving us handouts and that when the company leaves we will be left poorer, with unsuitable land and full of hate.”

Terraearth Resources has had, in the Regina S1 concession, 29 control and monitoring inspections by the Ministry of Environment between 2013 and 2022. In just one of them, carried out on February 3, 2022, more than 55 environmental non-compliances were detected, including the verification, at the time of the inspection, of direct discharges into the river, the lack of wastewater treatment ponds, 55 gallons of fuel in bad condition, and the lack of waste separation at the work fronts. Based on that inspection, operations were prohibited as of September 6 of the same year.

However, according to satellite images, between September 2022 and May 2023, three mining fronts have been expanded in the Shiguacocha area.

The river on which the community used to depend, the Chumbiyacu, which the Ikiam Amazon Regional University confirmed has 500 times more heavy metals than allowed, is still dead. The population lives on rainwater collected in blue plastic tanks placed on top of their wooden houses.

Patricio Villamil’s uncle also has leadership and together with three other families carried out this procedure in Quito to create a new board of directors behind his back.

In the meantime, Villamil sent to the Secretary of Human Rights a petition for revocation of the decisions taken that afternoon of February 21, 2021.

It took a year and four months of letters, reports, notifications, payments to lawyers, signatures, and mails before a ruling was issued in Villamil’s favor (partially) that annulled the minutes of the assembly of February 21 in which 9 members of the community were expelled, another president was chosen, and 40 more people (almost all of them with the last name Aguinda) were affiliated.

However, the Court of Justice of Napo also decided that the legal status of Shiwa Cocha, headed by Nelson Aguinda, could be maintained.

As this was happening in the judicial buildings, the families of the Shiwa Cocha community kept the key to the communal house built in 2020. When the sentence was handed down, Villamil got it back.

“Then, is the community called Shiguacocha or Shiwa Cocha?” I ask Villamil.

“Now both exist. We are 36 members in Shiguacocha and I am the president recognized by the Citizen Participation Council. I am de facto president, but not de jure, since I do not have legal status. The other four families, including my uncle’s, form Shiwa Cocha and have legal representation.”

Villamil says that despite the poverty of the community (eight out of ten people in the Carlos Julio Arosemena Tola canton live in extreme poverty on less than two dollars a day and have no access to drinking water), most of Shiguacocha’s members have paid fees of more than $100 to hire lawyers and defend themselves against the “other side,” which went as far as to request the deeds to their properties be taken from them.

“Not everyone has been able to pay the fee, so I asked for a loan that I am still paying. I don’t know with what money the others will pay so many lawyers,” says Villamil.

The residents of Shiguacocha say they will continue to fight until Terraearth Resources is sanctioned for the environmental and social damage it is leaving in its wake. “Even if it means selling every single one of our chickens, we are going to fight,” Villamil says.

So far there are no definite sanctions against the company by any public entity, beyond the technical reports of the Ministry of the Environment.

In December 2022, Shiguacocha organized a Christmas party. When they wanted to enter the communal house — the one that was built in minga with laughter, soccer, food, and beers — they realized that the locks had been changed. The families of Shiwa Cocha asked the police chief to keep the place locked.

“We couldn’t celebrate with the children,” laments Villamil. “There may be companies that comply with their obligations, but this mining company seems to be the work of the devil himself. They are not interested in families, they are not interested in the community, they are not interested in well-being. They are only interested in taking wealth at the cost of exploitation,” Villamil says over the phone before starting his shift as a security guard in another city because in his town there is no work, no fertile soil, no water.

InquireFirst again contacted attorney Cruz, who represented Terreaearth Resources at the September 23, 2022 hearing. Cruz said he did not know anything about the social division issue. InquireFirst also attempted to contact a company representative but did not get a response at the time of publication.

On October 31, 2022, Terraearth Resources received environmental permit approval from the Ministry of Environment, Water and Ecological Transition for the Tena Project, a concession of more than 17,297 acres in the Tena canton adjacent to the Carlos Julio Arosemena Tola canton where Shiguacocha is located.