September 5, 2019

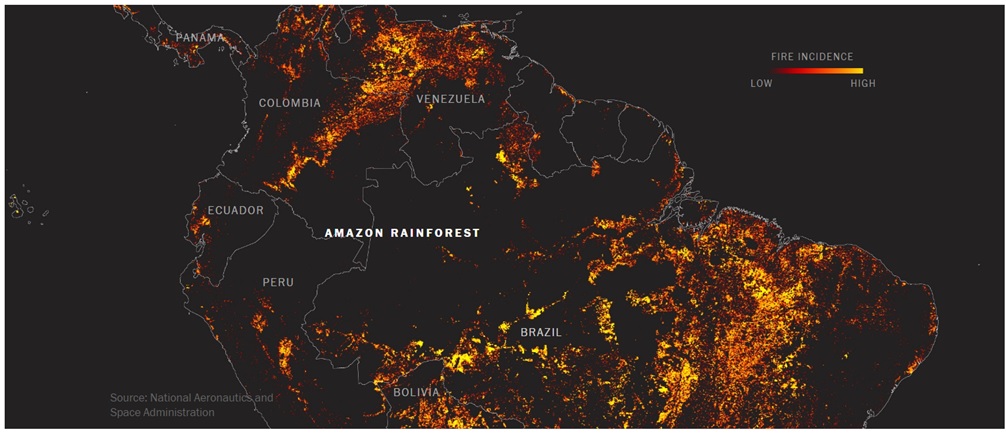

For weeks, we’ve seen headlines saying the Amazon rainforest is burning. But something unexpected happens when you map satellite data showing both the fires this year and those that have burned in the previous four years: The bulk of the forest remains almost entirely intact.

Confused? That’s because the heart of the Amazon is not actually on fire. Instead, most of the fires are burning at the fringes of the forest. That’s where the real story, and the real solution to these fires, lie.

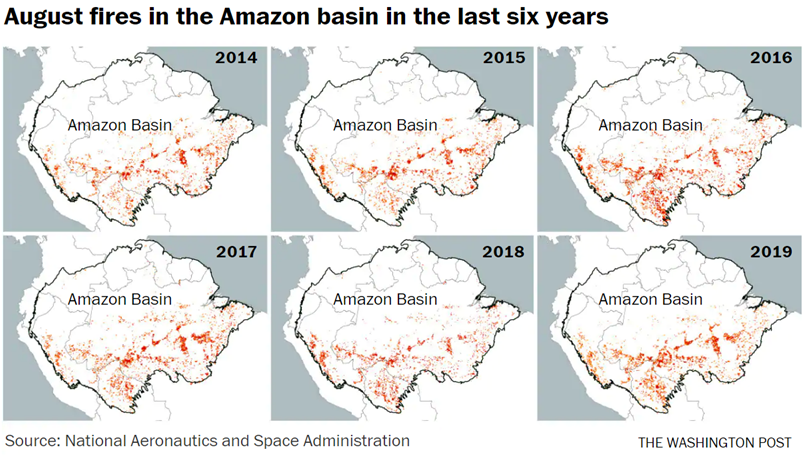

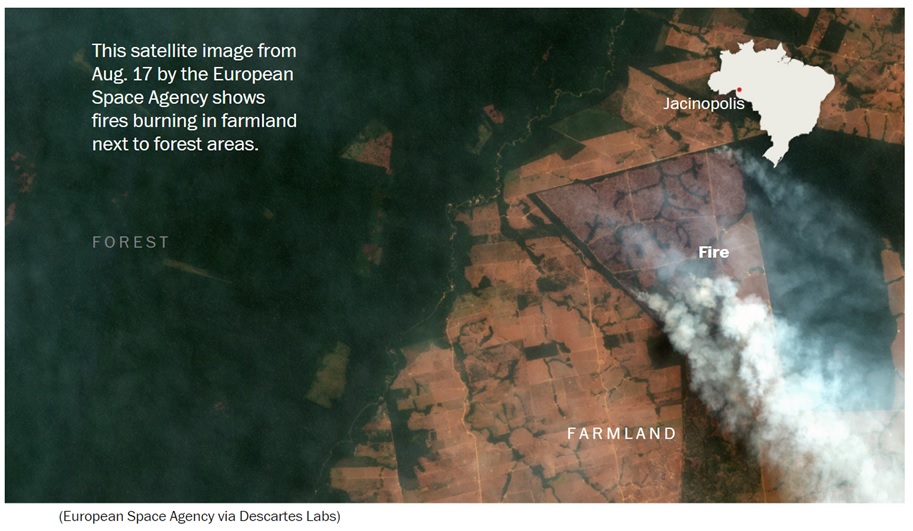

Fires are common in the region during this time of the year, as seen on the maps below. They are mostly a man-made event. These fires are set in areas that had already been deforested in previous years and are now being cleared for agriculture.

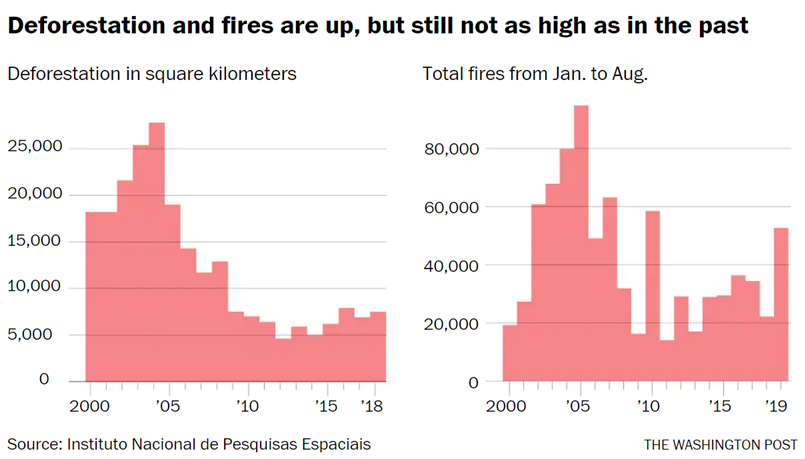

Brazil nearly doubled its arable land for intensive row cropping between 2000 and 2014, according to a recent study by researchers from the Department of Geographical Sciences at the University of Maryland. Much of the new cultivable land is a result of deforestation.

Earlier this decade, deforestation in Brazil slowed considerably, but more recently, both deforestation and the fires that go along with it have been rising. There were nearly three times as many fires this August as there were the previous August, affecting more than 10,000 square miles of land. Brazil is one of the world’s biggest generators of greenhouse gas emissions, and about 46 percent of the country’s emissions come from the slash and burn deforestation process.

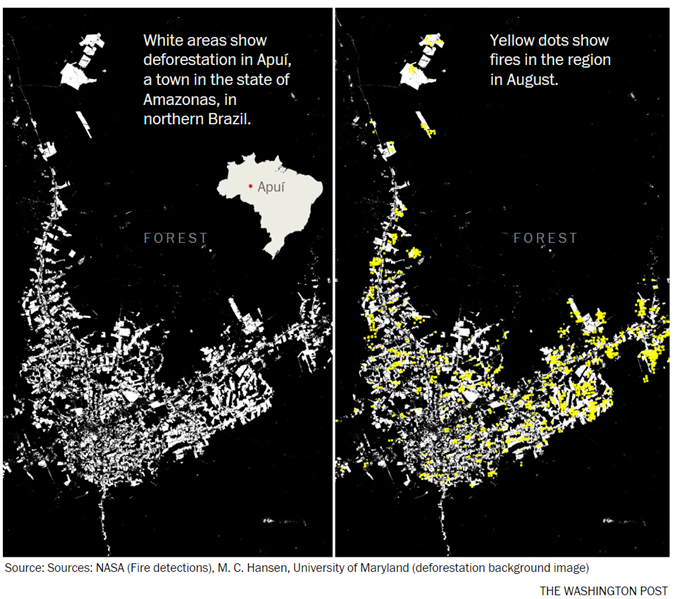

The maps below zoom in on the town of Apuí, in Amazonas state. The white areas on the first image show previously deforested areas. The yellow on the second image locates the fires last month. Most fires overlap previously deforested areas, a reminder that most of the fires are not in the forest but on its fringes.

The fires were so widespread last month that in São Paulo, Brazil’s largest city, smoke clouds originating hundreds of miles away turned the day to night. Soot and smoke are contaminating clouds, and some scientists believe that it could be reducing precipitation and altering the regional climate — and even that the deforestation-related fires could turn large parts of South America into a desert.

And to understand what’s driving this expansion of Brazilian cropland, it’s helpful to remember that Brazil’s economy has long relied on commodity exports, mostly from agriculture. With an unemployment rate at 12 percent — about 28.4 million people are without a job or underemployed — the country can ill-afford to back off one of its few thriving sectors.

In the past few years, Brazil became one of the world’s biggest producers of such proteins as soy and beef. The European Union is a key importer of Brazilian agricultural products, and China is an even bigger trading partner. The ongoing trade war between the United States and China has afforded Brazilian soy farmers an opportunity to outflank their U.S. competitors and lock down a vast new market. Meeting that demand is yet another incentive to clear more land for cultivation.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro inherited this economic dynamic. But he has been widely blamed for the fires because his policies exacerbate the problem. Even before taking office this past January, Bolsonaro announced plans to unravel the ministry responsible for protecting the environment. The idea was later scratched, but environmental protection have been weakened under his leadership. Bolsonaro’s government reduced the budget of Brazil’s environmental protection agency by 24 percent, fired employees and created a department to revise, reduce or cancel environmental fines.

Bolsonaro has bluntly rebuked other countries that he believes are trying to dictate to Brazilians how to handle their natural resources. Leaders of the Group of Seven nations did just that during their recent summit in France, even though they later remained silent about President Trump’s reported push to lift logging restrictions in a part of Alaska roughly as large as West Virginia.

The consequences of the fires in the Amazon know no borders, and neither do the forces that ignited them. If the developed nations want a greater say in the stewardship of the rainforest, they might need to provide more than the modest $20 million offered by the G-7 last month. They might need to pay for it in higher prices for agricultural imports. Most important, they might have to readjust their own consumption habits.

Bolsonaro, as he has on so many other occasions, is also missing the point — and an opportunity. If he really wants to revitalize Brazil’s economy, he could take advantage of the world’s renewed interest in the Amazon and ask developed countries just how much they’re willing to pay to help preserve it. Allowing further deforestation may be a tempting short-term economic lifeline, but this policy puts at risk the future of his country and of its neighbors around the globe.

*Tim Wallace has a PhD in geography from the University of Wisconsin at Madison and is currently a visual storyteller at Descartes Labs.

Extracted from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/09/05/were-thinking-about-amazon-fires-all-wrong-these-maps-show-why/