BBC

Camilla Costa

21 May 2020

The Amazon rainforest – which plays a vital role in balancing the world’s climate and helping fight global warming – is also suffering as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

Deforestation jumped 55% in the first four months of 2020 compared with the same period last year, as people have taken advantage of the crisis to carry out illegal clearances.

Deforestation, illegal mining, land clearances and wildfires were already at an 11-year high and scientists say we’re fast approaching a point of no return – after which the Amazon will no longer function as it should.

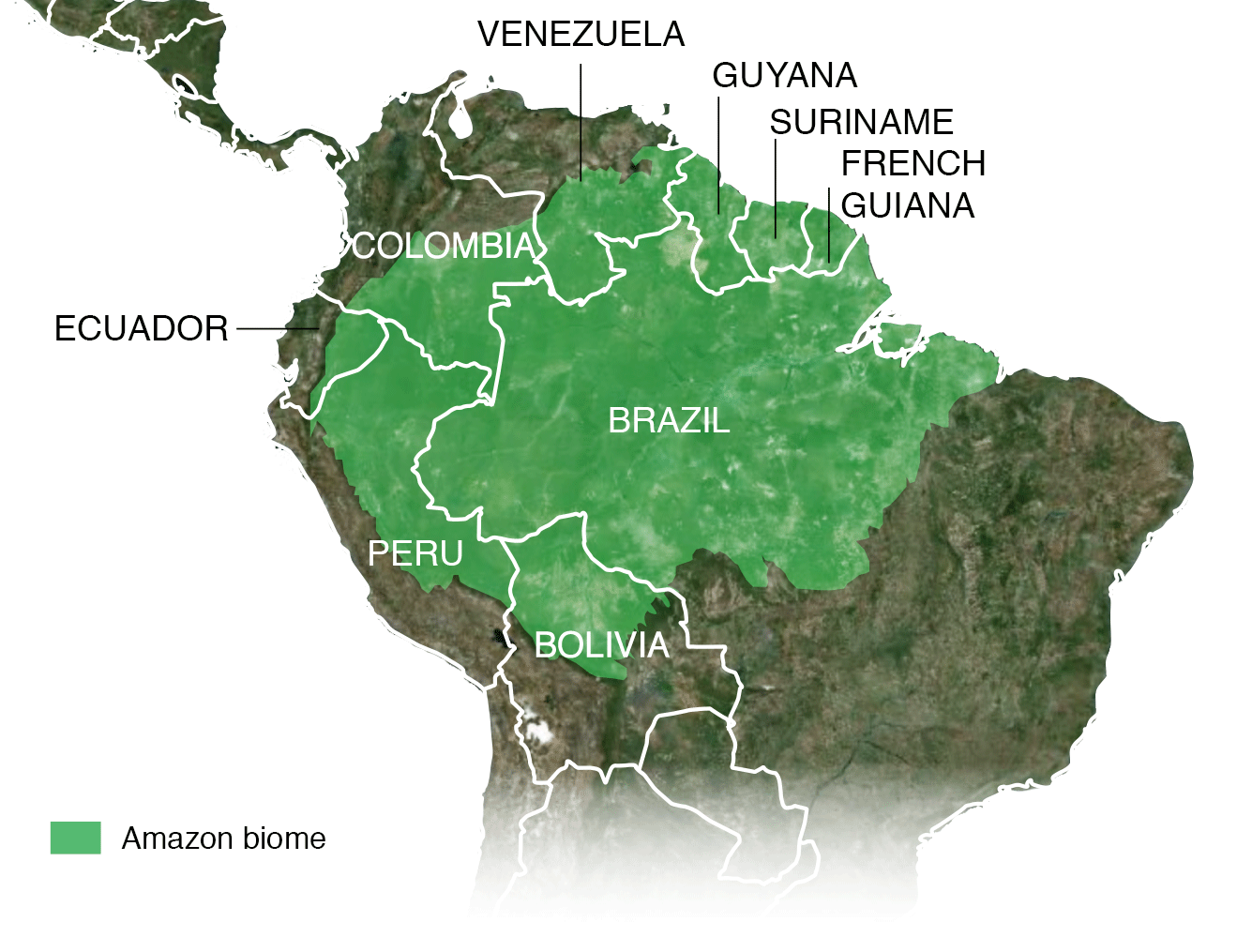

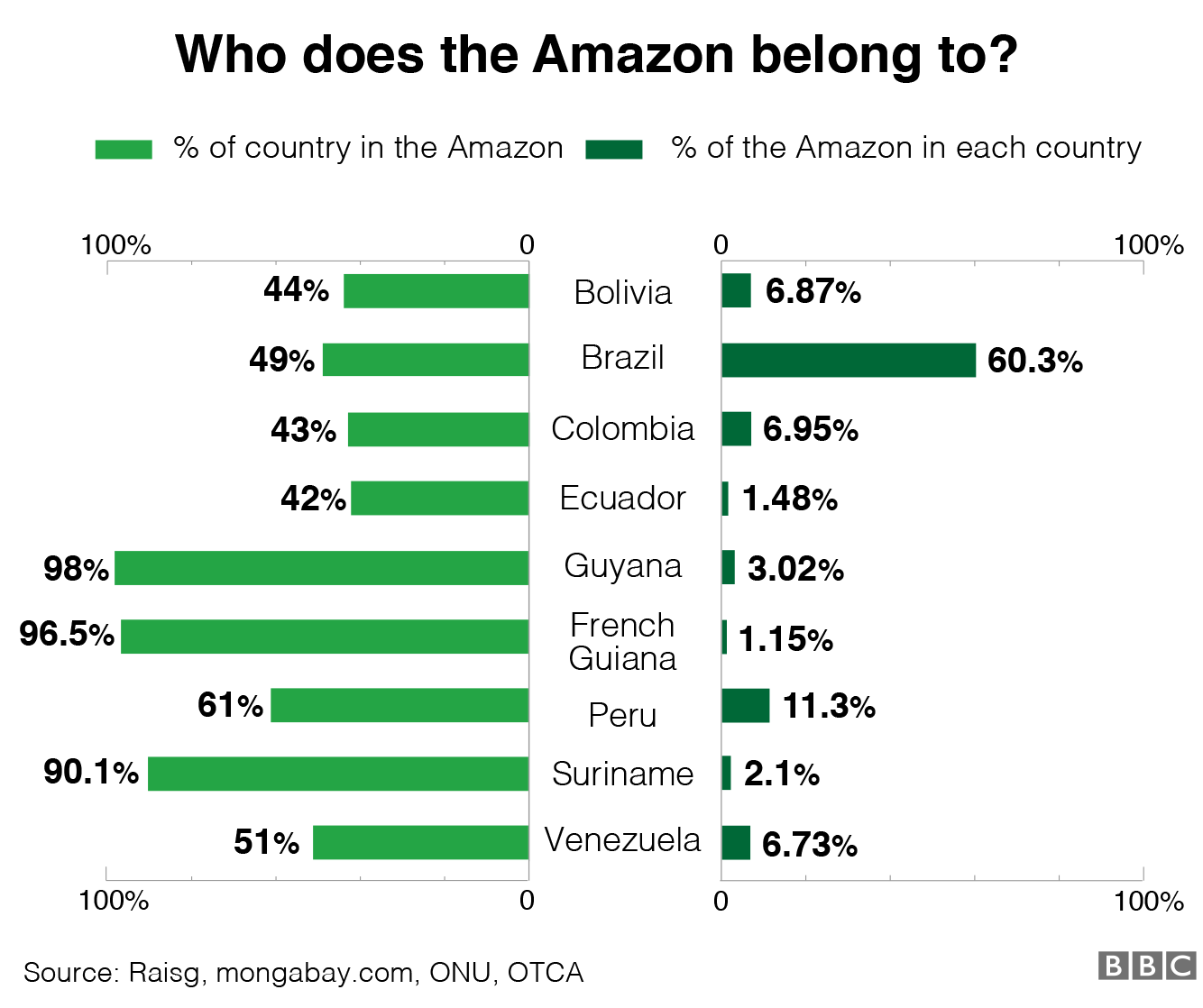

Here, we look at the pressures pushing the Amazon to the brink and ask what the nine countries that share this unique natural resource are doing to protect it.

Coronavirus and the forest

The largest and most diverse tropical rainforest in the world is home to 33 million people and thousands of species of plants and animals.

Since coronavirus spread to Brazil, in March, Amazonas has been the state to register Brazil’s highest infection rates – it also has one of the most underfunded health systems in the country.

As elsewhere, social distancing and travel restrictions have been imposed to limit the spread of the virus.

But many of the field agents working to protect reserves have pulled out, Jonathan Mazower, of Survival International, says, allowing loggers and miners to target these areas.

In April, as the number of cases rose and states started adopting isolation measures, deforestation actually increased 64% compared with the same month in 2019, according to preliminary satellite data from space research agency INPE.

Last year, an unprecedented number of fires devastated huge swathes of forest in the Amazon. Peak fire season is from July which some experts worry could coincide with the peak of the coronavirus crisis.

The Brazilian authorities are deploying troops in the Amazon region to help protect the rainforest, tackle illegal deforestation and forest fires. But critics say that the government’s rhetoric and policies could actually be encouraging loggers and illegal miners.

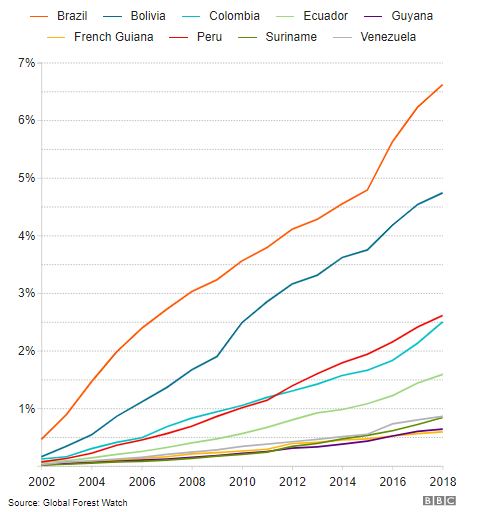

Even before this year’s spike in deforestation, the rate across the nine Amazon countries had continued to rise.

Brazil and Bolivia were among the top five countries for loss of primary forest in 2018 and both saw a dramatic increase in wildfires last year.

But that is not the only problem.

“To only speak of deforestation when we refer to the loss of the Amazon is what I call “the great green lie”,” says climate scientist Antonio Donato Nobre.

“The destruction of the Amazon rainforest up till now is much bigger than the almost 20% that they talk of in the media.”

To get a more complete sense of the scale of the destruction, Dr Nobre says it is necessary to take into account the figures for degradation.

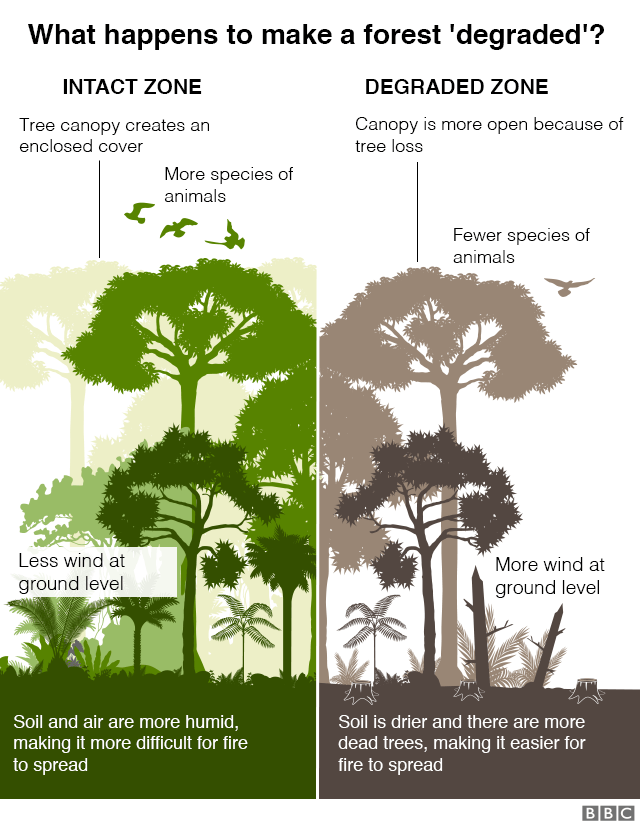

This happens when a combination of pressures on a stretch of forest – such as fires, logging or unlicensed hunting – make it hard for the ecosystem to function properly.

Even if an area does not lose all its trees and vegetation, degradation strips the rainforest of properties that are vital to the planet.

Scientists say that if we don’t reverse current levels of deforestation and degradation, the consequences of climate change could accelerate.

Not all deforestation is the same

The most common way of measuring deforestation is “tree cover loss” – where forest vegetation has been completely erased.

In 2018 alone, the tree cover loss in the Amazon reached four million hectares (40,000 sq km), according to Global Forest Watch.

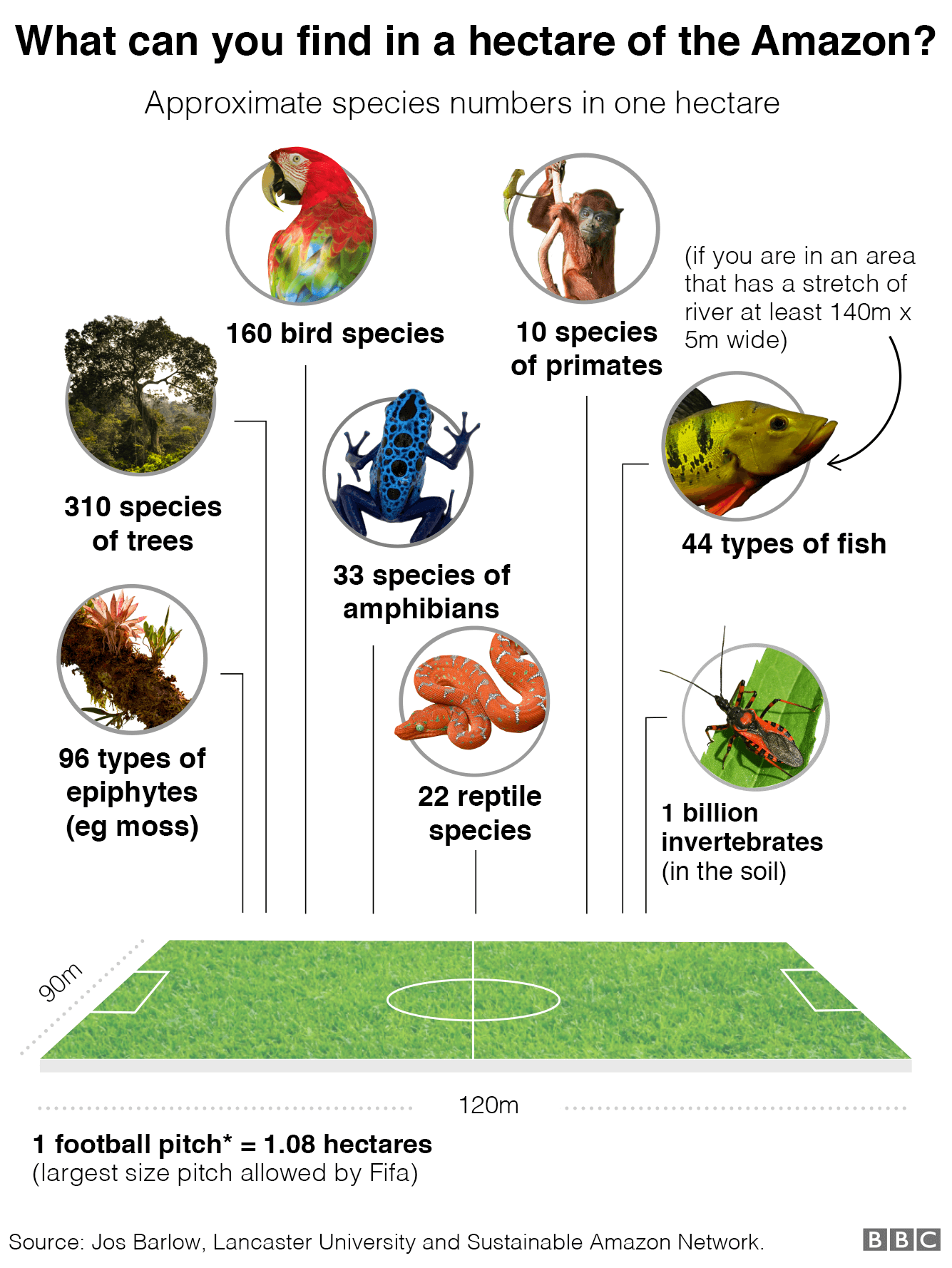

Almost half of this was primary forest – 1.7 million hectares of forest that was still in its original state and rich in biodiversity. Its destruction was the same as three football pitches of virgin forest being destroyed every minute in 2018.

This may seem insignificant – only 0.32% of the forest in the whole Amazon biome – but it is also a question of quality.

“Each hectare deforested means part of the ecosystem ceases to function and this affects the rest,” says Oxford University rainforest expert Erika Berenguer.

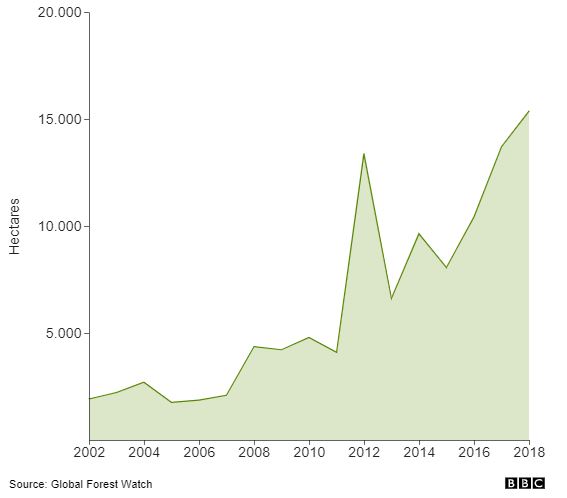

In the last 10 years, figures for primary forest loss have remained high or spiked in most of the Amazon nations.

What role do trees play?

Primary forest is home to trees that can be hundreds or even thousands of years old. They perform a powerful role in mitigating the effects of climate change, as they act as an enormous carbon dioxide store.

A small part of the CO2 absorbed by trees during photosynthesis is released into the atmosphere during respiration. The rest is transformed into carbon which the trees use to produce the sugars needed for their metabolism.

The older and larger the tree, the more carbon it stores.

According to Dr Berenguer, a large tree (with at least three metres circumference) can contain between three and four tonnes of carbon. This is the same as about 10 to 12 tonnes of CO2, or what a family car emits over four years.

” Many people believe that to make up for what we’ve lost in the Amazon, we just need to plant trees elsewhere. But that is not the case” Erika Berenguer, Oxford University

One of the direct effects of deforestation is that it releases CO2 stored in the forest. Forest fires or the decomposition of felled trees both transform the carbon within the tree back into gas.

For this reason, scientists fear that the Amazon will stop being a carbon store and will instead become a serious emitter of CO2, accelerating the effects of climate change.

A recent study claimed that 20% of the Amazon is already emitting more CO2 that it absorbs.

The (in)visible destruction of the Amazon

Experts like Antonio Nobre believe that deforestation does not show the full picture of what is being lost and we should also take into account “degradation”.

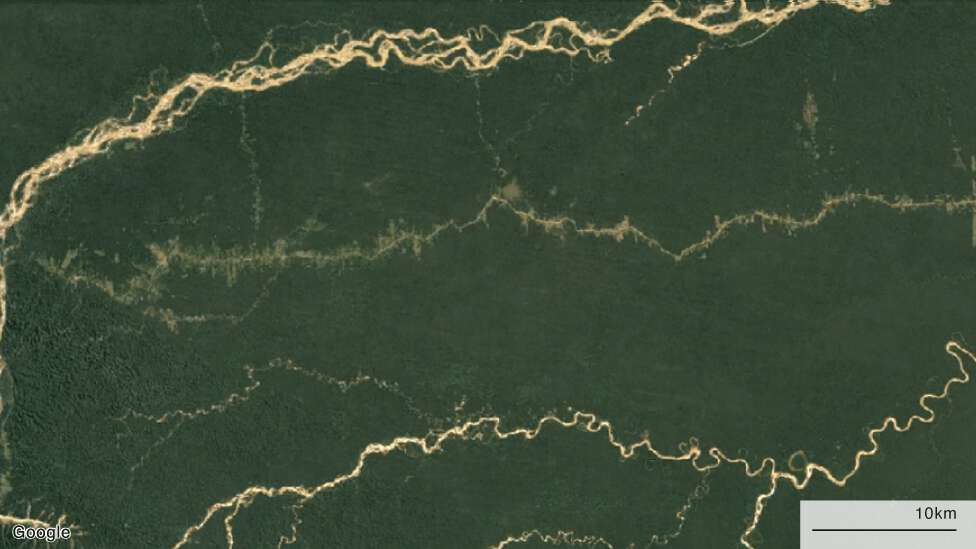

This phenomenon is as much the result of climatic events – such as drought, as human action – such as burning or illegal logging which strip the forest of its vital functions. However, seen from above, it may seem that the forest is still standing.

” We should not cut down another single tree in the Amazon region” Antonio Nobre, INPE

“Even though not all the vegetation is lost, the soil is drier and more fragile. This changes the microclimate of the forest and makes it easier for fires to spread because the soil heats up faster,” explains Dr Alexander Lees, Senior Lecturer in tropical ecology at Manchester Metropolitan University in the UK.

Scientists also warn that degradation is an important factor in releasing stored CO2. A new study by Raisg says 47% of all the emissions in the Amazon are as a result of degradation.

And in seven of the nine Amazon countries, they say, degradation is the main source of their carbon dioxide emissions.

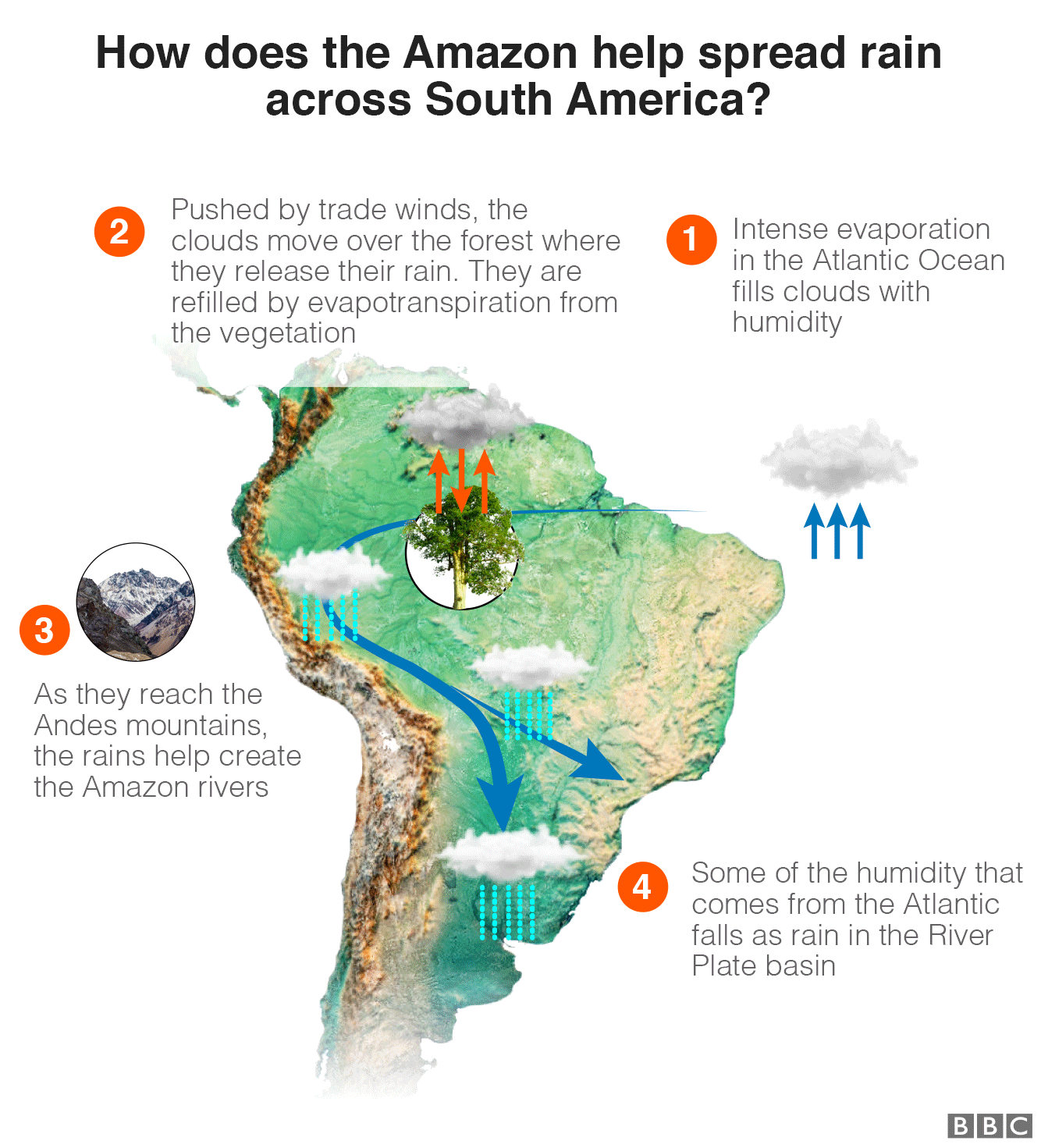

Degradation also makes the forest less efficient. It loses, for example, the ability to generate some of its own rain.

If we take the deforestation and degradation together, more than 50% of the Amazon no longer performs environmental services for the region’s climate, says Antonio Nobre.

Dr Nobre says the degraded areas of the Amazon are nearly twice as big as the deforested areas.

A recent report by the Colombian government confirms that between 2012 and 2015, its own Amazon region lost 187,955 hectares of forest to deforestation and 414,605 hectares to degradation – more than double.

So why don’t they talk about degradation when measuring forest loss in the Amazon?

“It is a difficult phenomenon to measure because although you can see degradation on satellite images, you need to have data from the ground to understand the real picture – whether that area is more or less degraded or is recovering,” says Alexander Lees.

Among the Amazon countries, only Brazil regularly publishes annual degradation figures. However, scientists from across the region are trying to produce the relevant data to form a wider picture of the current state of the forest.

What happens if we lose the forest?

If deforestation and degradation continue at current levels, the Amazon could stop working as a tropical ecosystem, even if some of it is still standing.

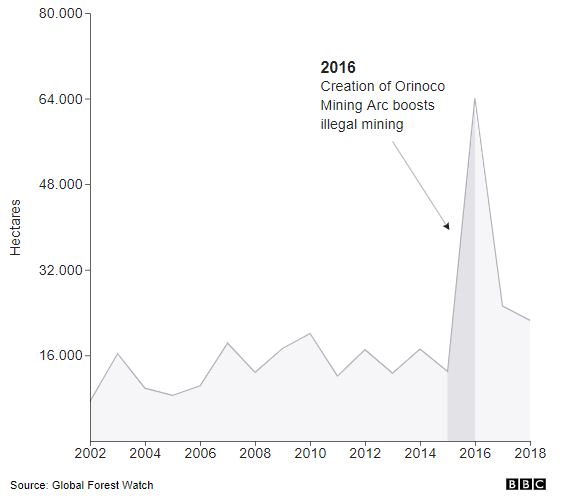

Annual loss of primary forest in the Amazon between 2002 and 2018

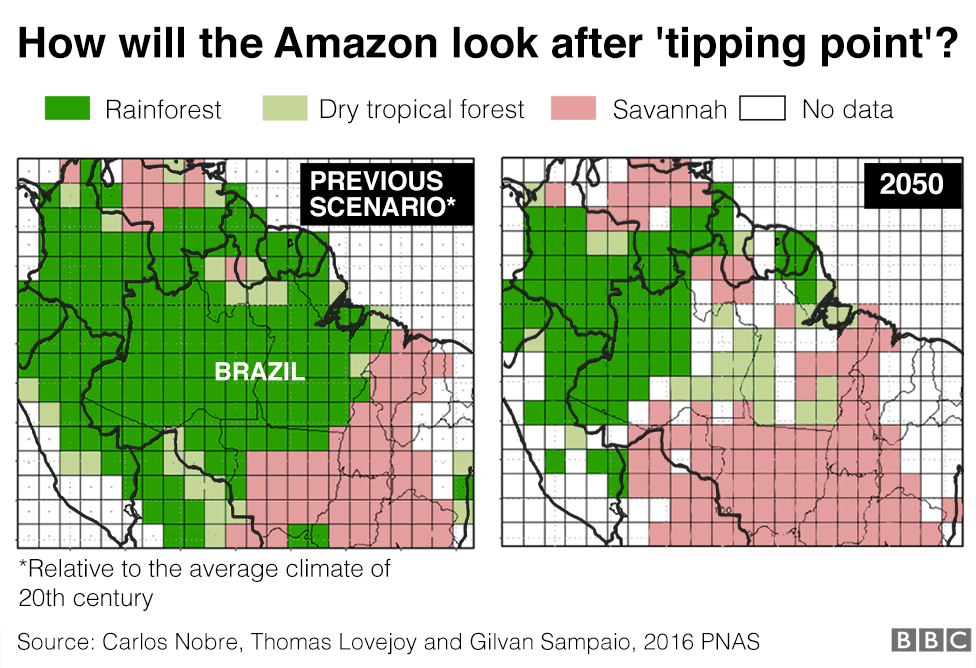

We could be dangerously close to what scientists call “the tipping point” – when the nature of the Amazon will completely change.

We could be dangerously close to what scientists call “the tipping point” – when the nature of the Amazon will completely change.

This will happen when total deforestation reaches between 20% and 25% – and that could happen in the next 20 or 30 years.

It would cause the length of the dry season and temperatures in the forest to increase. Trees would start to die and the tropical rainforest could become more like a dry savannah.

The projection, however, still does not take into account degradation because of the difficulty of measuring it across Panamazonas – the joint Amazon biome across the different national borders.

This means it could be even closer than they think. But what could happen after the tipping point?

Less rain

Scientists can’t say exactly what a sudden transformation of the Amazon rainforest would mean.

But Brazilian climatologist Carlos Nobre, says temperatures in the region could increase by 1.5-3C in the areas which become degraded savannahs. And that is without taking into account possible increases already caused by global warming.

This could have a catastrophic impact on the local economy. Less rain and higher temperatures mean less water for animals or growing crops like soya.

More disease

Some studies link deforestation to an increase in illnesses transmitted by mosquitoes, such as malaria and leishmaniasis.

The process of degradation could make the insects look for other sources of food and get closer to urban settlements.

And temperature increases could lead to more heat-related cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, says Beatriz Oliveira, from Brazil’s Climate Change Investigations Network (Red-Clima).

“Even if the conditions we have at the moment stay the same, temperatures in the Amazon region could increase by 8C, taking into account deforestation and global warming by 2070.

“Replacing the rainforest with another ecosystem, this increase could be even greater or could happen sooner.”

Can we prevent tipping point?

According to Carlos Nobre, there is a way.

“First, we should adopt a zero deforestation policy in Panamazonas, immediately, together with a reforestation programme in the south, south-east and east of the Amazon, which are the most vulnerable areas.”

“If we could restore 60,000 or 70,000 sq km in this large area, where the dry season is already much longer, we could help the forest get back to working better and it would be more resilient.”

That doesn’t seem an easy task in the near future.

What are the threats in the Amazon’s nine countries?

Deforestation and its causes are a major source of friction between the governments of the nine Amazon nations, environmentalists, companies and indigenous groups: the desire for economic development clashes, in the main, with the preservation of the Amazon and its native peoples.

It affects the ecosystem of the whole region, including those who are not part of the Amazon itself, and beyond.

Antonio Nobre says: “The ring made by central-southern Brazil and the River Plate basin would be a desert if it wasn’t for the Amazon.

“People have no idea what it would mean to lose this magnificent hydrological system.”

So what is driving deforestation in each of the Amazon nations, how much primary forest have they lost and what are their governments doing?

The fires which started in Bolivia in May 2019 destroyed almost two million hectares of forest, according to the Friends of Nature monitoring NGO.

Half of that was in protected areas, known for their wide biodiversity.

Environmentalists say Evo Morales’ government has promoted deforestation with policies of selling land in the Amazon region to businessmen and distributing it to farmers.

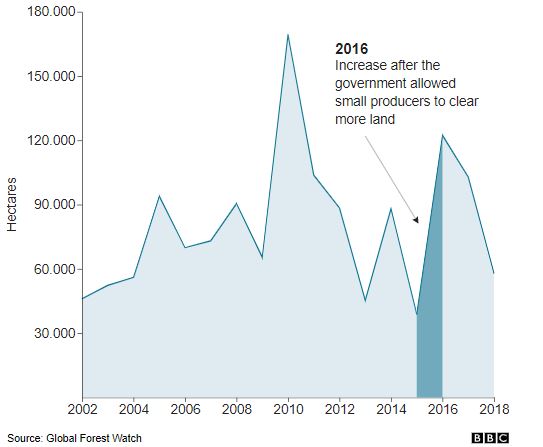

Loss of primary forest in Bolivia, 2002-18

The expansion of the farming frontier is mainly to encourage soya planting and cattle raising, in the hope of building exports for the Chinese market. In August 2019, Mr Morales celebrated the first beef exports to China from Santa Cruz.

The same region was responsible for nearly half of Bolivia’s soya production in 2018 and was most affected by the fires last year.

In response to criticism during the fires crisis, Morales halted land sales in Santa Cruz for what he called “an ecological pause”.

We asked the Bolivian environment ministry about its strategy to reduce deforestation, but have had no response.

-

2008: La Chiquitanía, in eastern Bolivia, is one of the main areas for cattle ranching and soya production in the country -

2010: While Evo Morales was in power, farmers and businesses received incentives to expand areas of production in the region -

2014: Controlled fires are a common practice in the deforestation process -

2016: A year after Evo Morales’ government quadrupled the area that small producers could clear, there is a rise in deforestation in the zone -

2018: Bolivia was one of the top five countries worldwide for primary forest loss, according to Global Forest Watch. In 2019, fires destroyed more than two million hectares of the Amazon

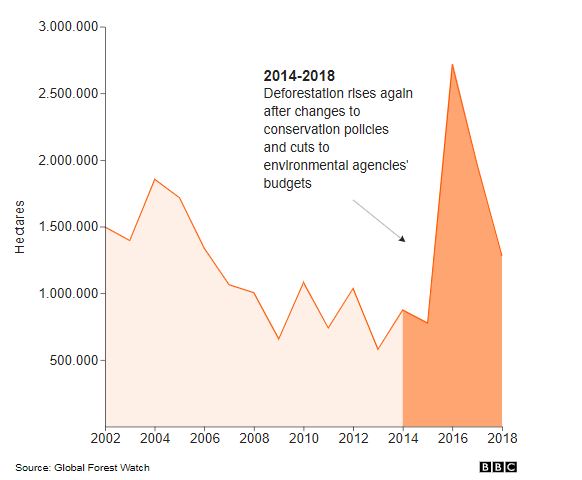

Brazil received international acclaim for the drop off in deforestation between 2004 and 2014 – an accumulated fall of 80% in almost 10 years.

But the loss of forest has once again started to rise.

Loss of primary forest in Brazil, 2002-18

In November 2019, the government published data confirming expert predictions: that between the middle of 2018 and the middle of 2019, deforestation in the Amazon had increased 30% in relation to the previous year.

In November 2019, the government published data confirming expert predictions: that between the middle of 2018 and the middle of 2019, deforestation in the Amazon had increased 30% in relation to the previous year.

They had cleared around 980,000 hectares (9,800 sq km), the largest area of forest cut down since 2008.

And these figures don’t take into account August 2019, when Amazon fires were at their worst.

President Jair Bolsonaro’s government claimed the fires were down to the dry season. But investigations by IPAM and the Federal University of Acre found otherwise.

According to their report, the Amazon fires are directly related to deforestation.

“After felling the trees, they leave it to dry for a few months then set fire to it to clear the vegetation. The land is then used to plant grass and create pastures,” says Erika Berenguer.

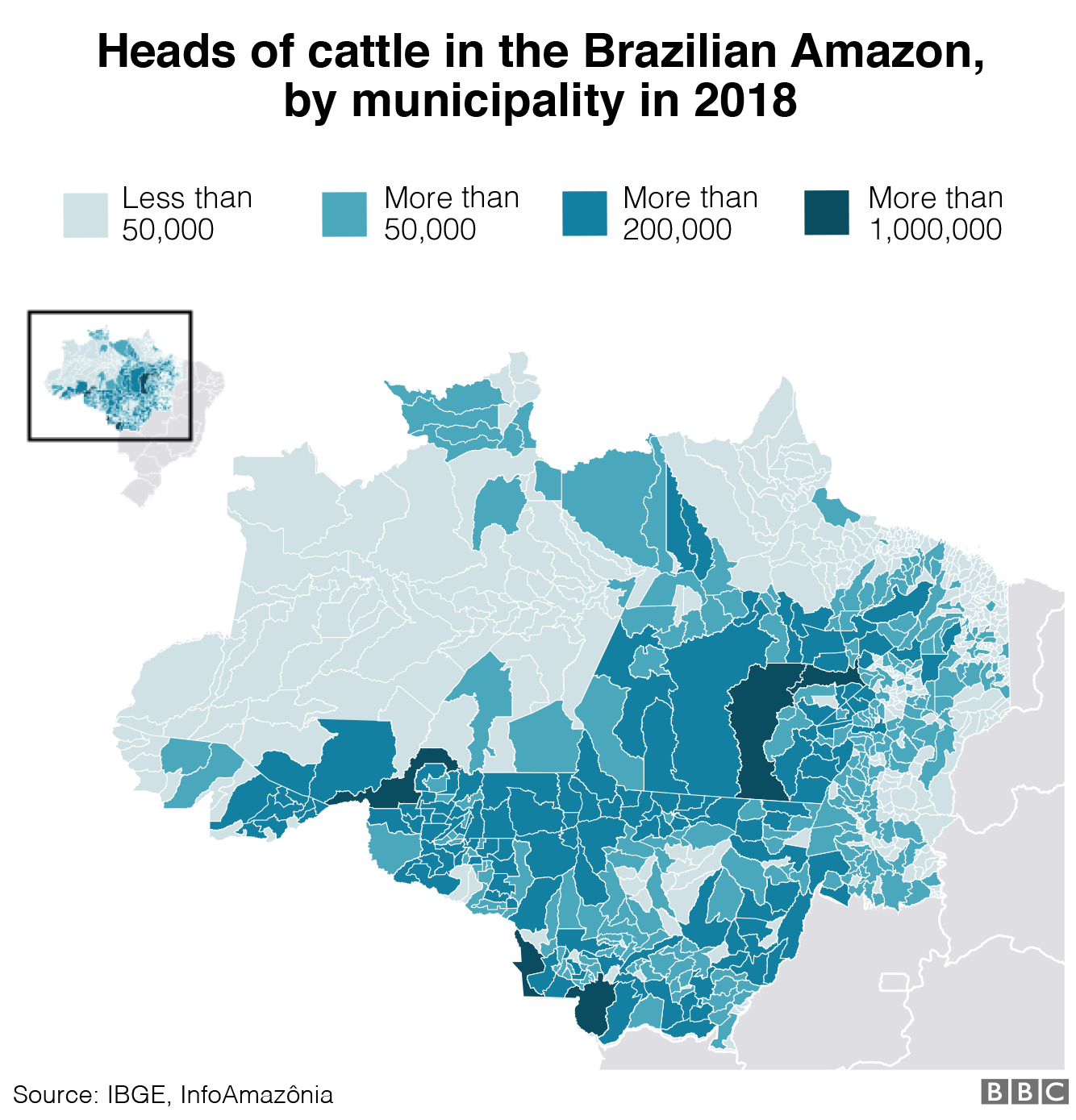

According to the FAO, 80% of tree loss in Brazil is directly or indirectly related to cattle farming. Brazil is the largest beef exporter in the world. It makes up 7% of the country’s GDP and 4.6% of exports.

Today, around 40% of the country’s cattle is raised in Amazon states. But that is only part of the story.

Around 60 million hectares of the Brazilian Amazon are considered public areas, or rather they have no legal purpose defined by the government.

They are not conservation areas, nor indigenous territories, for example. People clear this land, cut the trees down and put cattle on them, it’s the cheapest way to occupy them, says Stabile.

A patch of land without trees is worth more on the market.

“The primary use of deforested land in Brazil is cattle. But the aim is not necessarily to earn money from meat production but from the sale of land” Marcelo Stabile, of IPAM, the Amazon Environmental Research Institute

The next step in the chain is to illegally obtain a title deed for the land and sell it, says Mr Stabile. They then find another patch of forest and start again. The land is often sold to large-scale farmers and it is hard to tell which was cleared legally and what wasn’t.

The same happens in Colombia, Peru and Ecuador.

According to Mr Stabile and other investigators, Brazil could double or triple its number of cattle without felling another hectare of the Amazon rainforest.

“What’s happening is land speculation,” he says. “If the government defined these public areas, it would cease to be lucrative.”

Environmentalists and investigators say statements and policies from Bolsonaro’s government are encouraging clearances and the persecution of indigenous people.

Although the government denies this, the president has said he wants to end the “industry of environmental taxes” and believes the country has too many conservation areas. The government also wants to allow mining on land belonging to indigenous tribes.

Between January and September 2019, attacks and invasions of indigenous people’s land increased 40% on the previous year. The finger of blame is pointed at those involved in land clearance, logging and mining.

However, as the coronavirus crisis took hold in May, around 4,000 troops were mobilised in the Amazon against illegal logging and other activities until June, although that could be extended into the dry season to help with fire prevention.

Environment Minister Ricardo Salles said the coronavirus outbreak had “aggravated” the situation this year.

President Bolsonaro, however, has spoken against punitive measures taken against loggers and miners – such as the destruction of their equipment when it can’t be taken out of the forest. Critics say that sends a message that the government is on their side.

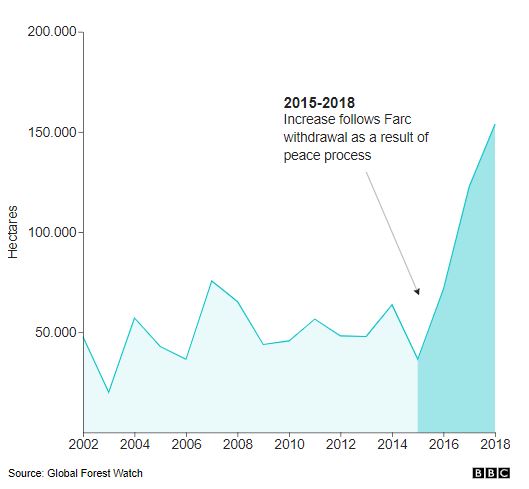

In 2017, the level of deforestation in Colombia was one of the biggest in the Amazon region and the highest in the country’s history. More than 140,000 hectares of forest was cleared, twice the previous year’s total.

This peak was a result of the peace accord with Farc rebels in 2016, which left a power vacuum in forested areas.

Loss of primary forest in Colombia, 2002-18

Community leaders said Farc had acted as a type of environmental police, controlling when farmers were allowed to clear the forest or burn for agriculture or cattle farming.

“Government officials wouldn’t come near the Amazon region because of Farc, who, for their own protection, had an interest in keeping the trees standing. So the rebels could establish strict rules,” said Rodrigo Botero, director of Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development.

However, Colombia is now facing a race to clear land in the Amazon led by large-scale farmers, local authorities, drug dealers and other paramilitary groups such as the ELN, says Botero.

There is a market for land and the government can’t stop it, he says.

The Colombian government formed a National Council for the Fight against Deforestation in an attempt to tackle the issue.

The group works to identify pockets of deforestation, the causes and what action is needed, according to the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development.

Laws passed in 2018 made the protection of water, biodiversity and the environment priority issues in matters of national security. The government can now intervene to protect areas in the Amazon national park from illegal activities.

They are also carrying out military operations against people clearing land and launching programmes which promote financial incentives for conservation.

But in 2018, deforestation rates only fell by 4%. By 2018, Colombian had lost around 11.7% of its original forest – 14% of which was in the last eight years.

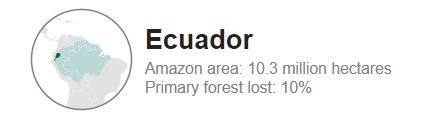

In the north of Ecuador, palm oil production is the main threat to the Amazon, experts say.

In the north of Ecuador, palm oil production is the main threat to the Amazon, experts say.

The oil is used worldwide in the industrialised production of food such as chocolate, cosmetics, cleaning products and fuels.

Ecuador is the second biggest producer of palm oil in Latin America, and the sixth worldwide.

The expansion of palm oil and cocoa plantations in the last 10 years is the main driver of deforestation, according to Global Forest Watch and Maap.

Loss of primary forest in Ecuador, 2002-18

This is particularly worrying because despite only covering about 2% of the Amazon biome, Ecuador has one of the most diverse parts of the forest. In just one hectare of the Yasuní park area, you’ll find 670 tree species – more than in the whole of North America.

This is particularly worrying because despite only covering about 2% of the Amazon biome, Ecuador has one of the most diverse parts of the forest. In just one hectare of the Yasuní park area, you’ll find 670 tree species – more than in the whole of North America.

Furthermore, according to a study by the country’s National Institute of Biodiversity, between 40% and 60% of the species of trees in Ecuador’s Amazon region are still unknown.

Mining boom

Mining projects and oil exploration in the Amazon have also made headline news in Ecuador.

One such project is Mirador, an open mine for copper, gold and silver which will be built in two Amazon provinces. It is the biggest project of its type in Ecuador – but not the only one.

The government says industrial mining in the region, carried out by a Chinese company, will be responsible and the income generated will allow investment in infrastructure locally.

However, investigators believe the activity could bring with it serious problems to the Amazon.

“As well as deforestation, we don’t know exactly where they are going to put the dams nor how they are going to monitor them,” said Carmen Josse, scientific director of the EcoCiencia Foundation.

“They are rugged areas with a lot of biodiversity. We don’t want an accident like Brumadinho, in Brazil” Carmen Josse, EcoCiencia Foundation

We asked Ecuador’s government about their strategy to prevent mining contributing to deforestation – but they have not responded.

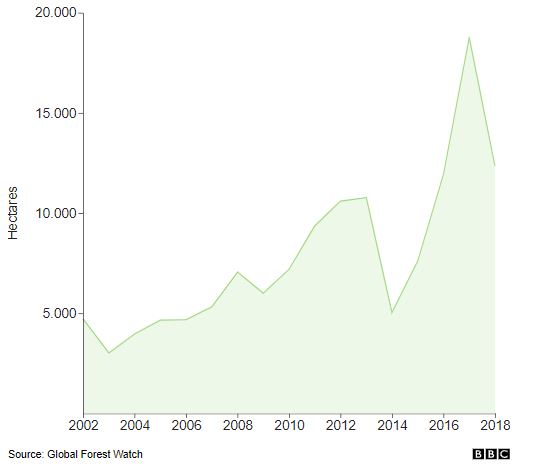

French Guiana soldiers search for illegal miners

Around 75% of it is virgin forest, which has had little or no intervention by humans, according to Global Forest Watch in 2016.

Among the Amazon territories it has the largest percentage of forest in protected areas – almost 50% – and the lowest levels of deforestation.

However, representatives of native people and environmentalists are worried by the advance of legal and illegal mining, encroaching on the protected zones.

Loss of primary forest in French Guiana, 2002-18

At the start of 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron suspended a gold mining megaproject within the Guianan Amazon National Park, which he had initially approved at the start of his tenure. The suspension was the result of national and international campaigns.

Despite this, illegal mining is the main threat to the park. Security forces have detected an increase in the number of illegal mines in the area since 2017.

With a population of less than 300,000 people, French Guiana has between 8,000 and 10,000 illegal miners. The rising price of gold since the 2008 financial crisis has sparked a rush to find the metal in the forests of the world.

“Most of the time, they’re poor kids from Brazil looking for easy money. They live in the forest for months and months,” explained Captain Vianney, who is leading the Foreign Legion’s operations against gold mining.

We asked the ministry of French overseas territories about the government’s strategy to combat deforestation but they have not replied.

Ninety five per cent of Guyana is covered by the Amazon.

The country proposes two ways of treating the forest which, for many, seem irreconcilable. On the one hand, it is looking for a way of exploiting it economically while at the same time selling itself as a Green State that protects the Amazon.

The annual rate of deforestation in Guyana is the lowest in the region – 0.051% in 2018, according to government figures.

Loss of primary forest in Guyana, 2002-18

Part of its success is due to strategies such as the creation of a forest management commission, which decides which trees can or cannot be cut down.

However, legal felling controlled by the government is still considered a factor that enables deforestation. According to environmentalists, licences for large international logging companies create access to virgin forest which illegal miners take advantage of.

Guyana’s Forestry Commission says it has not opened any new areas of the forest for legal felling since 2015.

In fact, some areas were taken back off the companies who had licences to exploit them and they have become conservation areas, the government said.

Illegal mining – mainly gold – is to blame for 85% of the forest loss, according to the Forestry Commission. Gold is the country’s main export.

The government says it has a “Green State development strategy” for the country which includes more investment in ecotourism and renewable energy, stricter limits on CO2 emissions and increasing forest conservation.

All this is funded by international agreements to preserve the Amazon and the discovery of huge oil reserves at sea.

A 2018 study found that despite making up only 4% of crops in the Amazon, palm oil was responsible for 11% of deforestation between 2007 and 2013. The oil is used worldwide to produce food, cosmetics and fuel.

After some palm oil producers were fined for deforestation, they started to buy land from small farmers who had already cleared the forest illegally, says Sandra Rios, geographical engineer with the Instituto de Bien Comun (IBC Peru).

“The State is slow in creating ways of monitoring, controlling and punishing deforestation by these and other means” Sandra Ríos, IBC Peru

We have asked Peru’s environment minister about their strategy to prevent deforestation – but they have not responded.

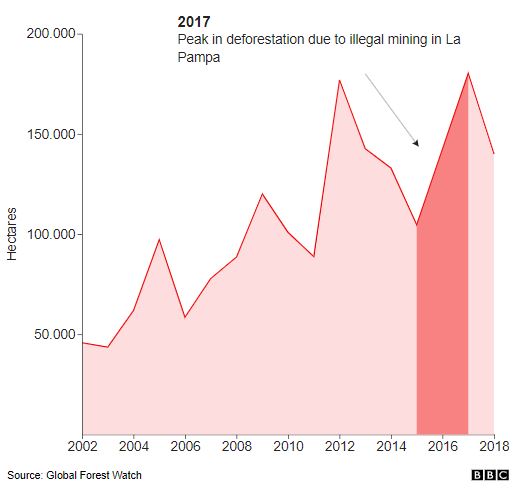

Illegal gold mining poses an increasing risk to the Peruvian Amazon. Peru is the biggest exporter of gold in Latin America, and the sixth worldwide. However, experts say up to 25% of its annual production comes from illegal mining.

Since 2006, Peru has been experiencing a new gold rush in the Tambopata Nature Reserve, one of the most biodiverse in the region, driven by rising gold prices and the construction of the Brazil-Peru Transoceanic Highway.

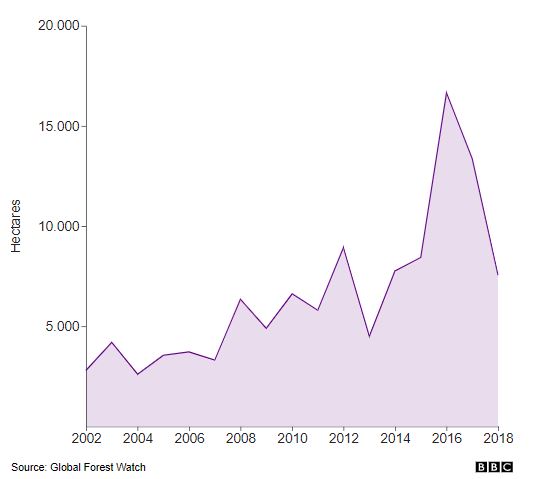

Loss of primary forest in Peru, 2002-18

The road, from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic, not only makes travelling easier, it also opens up previously inaccessible areas of the forest. The group of miners in the area, known as the La Pampa, has grown to have more than 5,000 members.

The miners strip the vegetation from the Amazon soil to look for gold. They use mercury to separate the precious metal from others, poisoning the waters and local animals in the process.

In 2017, the loss of forest as a result of mining reached its highest level since 1985, according to the Center for Amazonian Scientific Innovation (Cincia).

-

2007: Start of the Transoceanic Highway between Brazil and Peru beside the Tambopata Nature Reserve, of the the most diverse areas in the Amazon -

2010: When the road building finishes, the La Pampa enclave of illegal mining is set up -

2013: The road, according to scientists, gave access to more parts of the forest and increased deforestation to make way for mining in the area -

2016: A report by the Amazon Andes Monitoring Project says 350 hectares have been deforested as a result of illegal mining in the Tambopata reserve -

2018: At its peak, La Pampa had more than 5,000 active miners. In 2019, a military operation targeted the mining camp

With almost 94% of its territory within the Amazon, Suriname is one of the countries with the best track record of conservation in biome.

However, since 2012 Suriname has recorded an increase in the loss of forest, mainly as a result of gold mining.

Between 2000 and 2014, the extent of mining areas, generally on a small scale industrial or artisanal mines, increased by 893%, according to the Foundation for Forest Management and Production Control.

The government foundation says mining is responsible for 73% of the country’s deforestation.

Suriname is 10th in the world for gold production relative to its size. And that’s without mentioning illegal mining.

Loss of primary forest in Suriname, 2002-18

Most illegal mining takes place in remote areas of the forest, far from the authorities. It is believed that up to 60% of the gold miners in Suriname are Brazilians who cross the border illegally.

In some of the larger areas belong to indigenous tribes or descendents of slaves, mining has become the main source of income for families.

There are no current official figures available for deforestation in Venezuela, but monitoring by local and international scientists show forest loss has increased in the last few years – especially since the creation of the Orinoco Mining Arc.

With the dramatic fall in oil prices and production in Venezuela since 2014, the Maduro government has focused its attention at states rich in minerals – such as the Amazon.

Venezuela has the sixth largest natural gold reserve in the world, with around 7,000 tonnes.

The mining arc, created in 2016, allowed licences for mining precious metals such as gold, diamonds and coltan (a combination of columbite and tantalite used in the production of mobile phones) across an area of 112,000 sq km, about 12% of the country.

The area also covers natural landmarks, forest reserves, an Amazon national park and at least four designated indigenous territories.

“The Orinoco zone is traditionally a mining area, even the indigenous people did it,” says ecologist Peláez, from the NGO Provita.

“But the law, in some ways, legalised forms of mining that were already in place and did not help reduce activity. This has had an enormous impact on the environment and the local population.”

Maduro’s plan was to grant concessions to foreign mining companies which would have to form businesses together with state-owned companies in order to operate in the area.

In practice, according to Mr Peláez, this resulted in an exponential growth in small-scale mining.

In 2018 alone, according to the Central Bank of Venezuela, the state bought 9.2 tonnes of gold on the internal market – the same as the total amount for 2011-2017.

Loss of primary forest in Venezuela, 2002-18

“The gold that is there is of very poor quality, it’s dirty,” says Mr Peláez. “The amount that is coming out of the ground is very small.”

People are destroying the forest and digging wherever they can. They’re leaving sterile sand where nothing can grow. The deforestation in this zone is irreversibleCarlos Peláez, Provita

Mining is producing tonnes of sediment that is accumulating in the country’s main rivers. The use of mercury to separate gold from impurities, is poisoning rivers and indigenous people.

Venezuela has the most illegal mines in the Amazon, according to a study by Raisg. There are 1,899 illegal mines, concentrated in the Orinoco mining arc.

In the midst of Venezuela’s political crisis, the National Assembly tried to repeal the law that created the Orinoco Mining Arc and even labelled it “ecocide” or a crime against the environment.

We’ve asked three government ministries about the strategy to reduce deforestation in the zone, but none have responded.

Credits

Reporting: Camilla Costa

Text: Camilla Costa and Carol Olona

Design and graphics: Cecilia Tombesi

Production: Marta Martí and Marcos Gurgel

Translation: Dominic Bailey

Thanks to: Carlos Nobre, Antonio Nobre, Red Amazonía Sustentable, Red Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georeferenciada (Raisg), Júlia Jacomini, Gustavo Faleiros, Infoamazônia, Thiago Medaglia, Erika Berenguer, Rodrigo Botero, Mikaela Weisse, Global Forest Watch.

Taken of: https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-51300515